Nov

24

Understanding How Alkali Metal Doped Solar Cells Work

November 24, 2020 | Leave a Comment

Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology (GIST) scientists have discovered that the amount of alkali metal introduced into crystals of flexible thin-film solar cells influences the path that charge carriers take to traverse between electrodes, thereby affecting the light-to-electricity conversion efficiency of the solar cell.

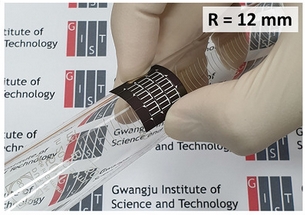

A digital camera image of a flexible CZTSSe solar cell. Image Credit: GIST. Click image for the largest view.

The press release asserts that given the immense application potential that such solar cells have today, this finding could be key to ushering in a green future.

Professor Dong-Seon Lee of GIST in Korea said, “When eco-friendly, inexpensive, versatile, and efficient solar cells are developed, all thermal and nuclear power plants will disappear, and solar cells installed over the ocean or in outer space will power our world.” His highly optimistic view of the future mirrors the visions of many researchers involved in the effort to improve solar cells.

Over the research history scientists have come to realize that doping – distorting a crystal structure by introducing an impurity – polycrystalline solar cells made by melting together crystals called CZTSSe with earth-abundant and eco-friendly alkali metals, such as sodium and potassium, can improve their light to electricity conversion efficiency while also leading to the creation of inexpensive flexible thin-film solar cells that could find many applications in a society that is increasingly making wearable electronics commonplace.

But why doping improves performance is yet unknown.

In a recent paper published in Advanced Science, Prof Lee and team reveal one part of this unknown. Their revelations come from their observations of composition and electric charge transport properties of CZTSSe cells doped with layers of sodium fluoride of varying thickness.

Upon analyzing these doped cells, Prof Lee and team saw that the amount of dopant determined the path that charge carriers took between electrodes, making the cell either more or less conductive. At an optimal doped-layer thickness of 25 nanometers, the charges flowed through the crystal via pathways that allowed for maximum conductivity. This in turn, the scientists hypothesized, affected the “fill factor” of the cell, which indicates the light-to-electricity conversion efficiency. At 25 nanometers, a record fill factor of 63% was obtained, a notable improvement over the previous limit of 50%. The overall performance was also competitive with this amount of doping.

These findings provide insight into CZTSSe and other polycrystalline solar cells, paving the way for improving them further and realizing a sustainable society. But the competitive performance of the solar cell that yielded these findings gives it real-world applications more tangible to us common folks, as Prof Lee explains: “We have developed flexible and eco-friendly solar cells that will be useful in many ways in our real lives, from building-integrated photovoltaics and solar panel roofs, to flexible electronic devices.” Given the bold vision that Prof Lee carries, perhaps a green economy is not too far away.

This is definitive work on getting thin film solar cells more efficiency deserving some attention and work on introducing it to scaling. There is also a noticeable enthusiasm in the team and the press release that evokes a smile and hope the dream gets closer to reality!