Jan

25

Superconductivity Shown In Graphene

January 25, 2017 | Leave a Comment

University of Cambridge St John’s College researchers have shown for the first time the intrinsic ability of graphene to superconduct (or carry an electrical current with no resistance). These results further widen the potential of graphene as a material that could be used in fields such as energy storage, high-speed computing, and molecular electronics.

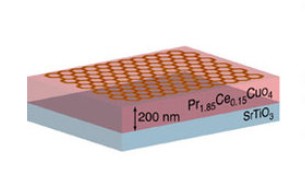

Schematic of SLG (hexagonal lattice) on PCCO/STO. Image Credit: University of Cambridge. Click image for the largest view.

The finding, reported with a paper published in Nature Communications, further enhances the potential of graphene, which is already widely seen as a material that could revolutionize industries such as healthcare and electronics. Graphene is a two-dimensional sheet of carbon atoms and combines several remarkable properties; for example, it is very strong, but also light and flexible, and highly conductive.

Since graphene’s discovery in 2004, scientists have speculated that it may also have the capacity to be a superconductor. Until now, superconductivity in graphene has only been achieved by doping it with, or by placing it on, a superconducting material – a process which can compromise some of its other properties.

Described in the new study, researchers at the University of Cambridge managed to activate the dormant potential for graphene to superconduct in its own right. This was achieved by coupling it with a material called praseodymium cerium copper oxide (PCCO).

Superconductors are already used in numerous applications. Because they generate large magnetic fields they are an essential component in MRI scanners and levitating trains. They could also be used to make energy-efficient power lines and devices capable of storing energy for millions of years.

Superconducting graphene opens up yet more possibilities. The researchers suggest, for example, that graphene could now be used to create new types of superconducting quantum devices for high-speed computing. Intriguingly, it might also be used to prove the existence of a mysterious form of superconductivity known as “p-wave” superconductivity, which academics have been struggling to verify for more than 20 years.

The research was led by Dr Angelo Di Bernardo and Dr Jason Robinson, Fellows at St John’s College, University of Cambridge, alongside collaborators Professor Andrea Ferrari, from the Cambridge Graphene Center; Professor Oded Millo, from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and Professor Jacob Linder, at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim.

Dr Robinson said, “It has long been postulated that, under the right conditions, graphene should undergo a superconducting transition, but can’t. The idea of this experiment was, if we couple graphene to a superconductor, can we switch that intrinsic superconductivity on? The question then becomes how do you know that the superconductivity you are seeing is coming from within the graphene itself, and not the underlying superconductor?”

Similar approaches have been taken in previous studies using metallic-based superconductors, but with limited success. Dr Di Bernardo explained, “Placing graphene on a metal can dramatically alter the properties so it is technically no longer behaving as we would expect. What you see is not graphene’s intrinsic superconductivity, but simply that of the underlying superconductor being passed on.”

PCCO is an oxide from a wider class of superconducting materials called “cuprates.” It also has well-understood electronic properties, and using a technique called scanning and tunnelling microscopy, the researchers were able to distinguish the superconductivity in PCCO from the superconductivity observed in graphene.

Superconductivity is characterized by the way the electrons interact: within a superconductor electrons form pairs, and the spin alignment between the electrons of a pair may be different depending on the type – or “symmetry” – of superconductivity involved. In PCCO, for example, the pairs’ spin state is misaligned (antiparallel), in what is known as a “d-wave state.”

By contrast, when graphene was coupled to superconducting PCCO in the Cambridge-led experiment, the results suggested that the electron pairs within graphene were in a p-wave state. “What we saw in the graphene was, in other words, a very different type of superconductivity than in PCCO,” Robinson said. “This was a really important step because it meant that we knew the superconductivity was not coming from outside it and that the PCCO was therefore only required to unleash the intrinsic superconductivity of graphene.”

It remains unclear what type of superconductivity the team activated, but their results strongly indicate that it is the elusive “p-wave” form. If so, the study could transform the ongoing debate about whether this mysterious type of superconductivity exists, and – if so – what exactly it is.

In 1994, researchers in Japan fabricated a triplet superconductor that may have a p-wave symmetry using a material called strontium ruthenate (SRO). The p-wave symmetry of SRO has never been fully verified, partly hindered by the fact that SRO is a bulky crystal, which makes it challenging to fabricate into the type of devices necessary to test theoretical predictions.

Dr Robinson explained, “If p-wave superconductivity is indeed being created in graphene, graphene could be used as a scaffold for the creation and exploration of a whole new spectrum of superconducting devices for fundamental and applied research areas. Such experiments would necessarily lead to new science through a better understanding of p-wave superconductivity, and how it behaves in different devices and settings.”

The study also has further implications. Dr Di Bernardo added that for example, it suggests that graphene could be used to make a transistor-like device in a superconducting circuit, and that its superconductivity could be incorporated into molecular electronics. “In principle, given the variety of chemical molecules that can bind to graphene’s surface, this research can result in the development of molecular electronics devices with novel functionalities based on superconducting graphene,” Di Bernardo said.

This is extraordinary news. The p-wave has been an item of considerable curiosity for decades. That makes two, the one in 1994 that may be one and this one which is a highly probable. The p-wave surely looks like its going to be real and graphene looks like the leading candidate to get it done. The outlook then expands into the p-wave field, too. Congratulations to this international team!