Nov

1

Fusion News Has a Big Week

November 1, 2016 | Leave a Comment

The American Physical Society had a major news day last Friday with noteworthy and informative presentation announcements for their annual meeting in San Jose, California. The four announcements deal with progress on measuring controlling and building plasma devices. These topics are critical to progress because plasma is very hot, usually under pressure and in high speed motion. Its not a good thing at all when it gets out of hand. Here are two, another one posts tomorrow and the third this Thursday.

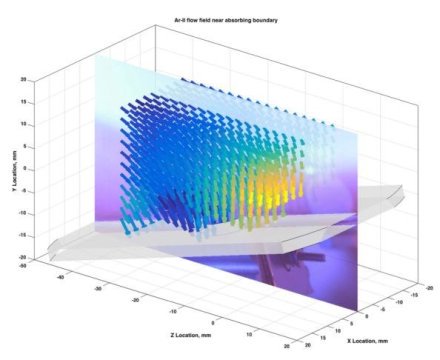

Understanding how this process occurs, and how scientists and engineers can prevent it, is critical to the development of the next generation of energy and space exploration technologies. The measurements performed at WVU in a “helicon” plasma are the first ever 3D ion flow fields mapped in a volume.

Measured flow field of ions in a plasma overlaid on visual image of the system. Image Credit: West Virginia University. Click image for the largest view.

The measurements show how plasmas in fusion tokamak devices and Hall thruster spacecraft engines accelerate parallel to the wall prior to impact. This causes the walls of these devices to erode more rapidly than previously thought, limiting their lifetimes. This flow is surprising because it is not predicted in theoretical models. The researchers are currently investigating the reasons for this behavior, looking at aspects of the plasma that were assumed to be unimportant in previous models.

These results, including the first fully 3D flow measurements, were presented at the 2016 American Physical Society – Division of Plasma Physics meeting in San Jose.

General Atomics scientist Nicholas Eidietis explained, “We have to quickly cool a 100-million degree gas undergoing fusion in roughly 1/1000 of a second. So when you have to shut down a fusion plasma that fast you have to be very careful of where all that energy is going to go.”

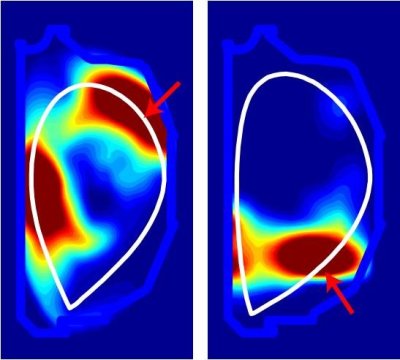

Extinguishing these fusion fires converts the plasma heat into an intense flash of light. Ideally, this intense flash uniformly illuminates the interior wall of the fusion device to avoid focusing too much energy on any one location, where it could cause damage. It’s the difference between a 50-watt light bulb and a 50-watt laser: Both produce the same amount of power, but only one will melt metal and damage the fusion reactor. The complicated physics of how the neon gas is injected from localized valves and spreads around inside the plasma, how the plasma heats the neon, and how the neon sheds the heat as light has recently been modeled by a team working at the DIII-D National Fusion Facility in San Diego.

Comparison of experimentally measured radiated power emission patterns inside the DIII-D tokamak with upper gas injection (left) and lower gas injection (right). Arrows indicates gas valve locations, the white border represents the plasma boundary, and the light blue border shows the vacuum vessel. Red coloring indicates the strongest emission, blue weakest.

Image Credit: General Atomics. Click image for the largest view.

The physics models simulate the complex interaction of the fusion plasma and injected neon gas in the DIII-D tokamak experiment. A controlled rapid cooling of the plasma is most likely to be needed if there is a loss of equilibrium caused by the growth of unwanted helical bundles of magnetic field called islands. In DIII-D experiments, pre-existing islands do not appear to impede the overall effectiveness of plasma cooling, but simulations indicate that details of the relative position between the island and the injection location might still affect the spreading of the neon. One of the most important findings of the simulations is that the neon spreading speeds up when the original island breaks up into a series of smaller islands.

In experiments researchers also showed that neon spreads more uniformly when it’s introduced near the top of the device instead of the bottom, increasing the desired uniformity of plasma cooling.

Val Izzo of University of California-San Diego (UCSD), who, along with Eidietis, led the team of UCSD and General Atomics researchers said, “This modeling is essential to help us understand what we are seeing in present fusion experiments so that we can confidently predict how a thermal quench will occur in ITER.”

The team’s results are also presented at the annual conference of the American Physical Society Division of Plasma Physics that ends November 4th.

This is highly useful research that may well apply to many fusion efforts. Yet tomorrow and Thursday a couple really interesting ones come up.