Feb

25

A Major Cornerstone Set In Superconductivity

February 25, 2016 | Leave a Comment

Settling a 20-year debate in the field, they found that a mysterious quantum phase transition associated with the termination of a regime called the “pseudogap” causes a sharp drop in the number of conducting electrons available to pair up for superconductivity. The team hypothesizes that whatever is happening at this point is probably the reason that cuprates support superconductivity at much higher temperatures than other materials – about half way to room temperature.

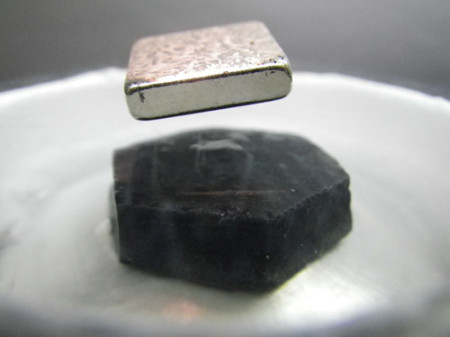

Levitation Using Superconductivity. Image Credit: University of Waterloo. Click image for the largest view.

CIFAR senior Fellow Louis Taillefer said, “It’s very likely that the reason superconductivity grows in the first place, and the reason it grows so strongly, is because of that critical point.”

The new findings have been published in Nature.

Taillefer, the director of CIFAR’s program in Quantum Materials, collaborated with his team and CIFAR’s Cyril Proust (Laboratoire National des Champs Magnétiques Intenses), Doug Bonn, Walter Hardy and Ruixing Liang (all three University of British Columbia). The study combined the University of British Columbia’s expertise in making copper-oxide materials known as cuprates, the Université de Sherbrooke’s expertise at probing them, and the powerful magnetic fields produced at the Toulouse lab.

The team’s work is part of a global effort to harness superconductivity – the transmission of electricity with zero resistance in certain materials – to greatly improve power efficiency in many technologies. Cuprates are the most promising materials for that purpose right now, but the community is faced with a formidable physics problem: understanding the mysterious “pseudogap” phase.

Taillefer explained the situation, “That’s been the debate for 20 years – what is going on in the pseudogap phase?”

The mystery has remained unsolved for so long mainly because when superconductivity kicks in, it becomes difficult to study what behaviors are taking place beneath it. With a magnetic field two million times that of Earth’s, the team of scientists managed to wipe out superconductivity in cuprate samples and look closely into the pseudogap phase at temperatures near absolute zero (- 273º C).

At the point of instability where the pseudogap sets in, the electronic structure of cuprates undergoes a radical change. The number of available electrons plummets six-fold. This marks a quantum phase transition – a fundamental change of behavior within the material.

The scientists believe this new work will create a major shift in the focus of future research, and will lead to a new understanding of the properties of superconductors. Taillefer says this finding points the way to discovering the nature of the critical point and its fluctuations, and then exploring how to make superconductivity work at room temperature.

The discovery follows intense research on the pseudogap mystery, after the same group of CIFAR researchers discovered the first signs of strange behavior by observing quantum oscillations in 2007. “The development at Toulouse of very low noise measurements, crucial for the discovery of quantum oscillations in 2007, and now recently the design and construction of our 90 T magnet, together opened up a new window of capability, allowing us to look directly at the pseudogap critical point,” said Cyril Proust.

CIFAR Associate Fellow Subir Sachdev (Harvard University) says the findings validate some of his recent theoretical research and set a clearer direction for future investigation that zooms in on this critical point.

“This gets me very excited about working on the theory of such a critical state,” Sachdev said. “The new experiments really sharpen the picture.”

Taillefer said the research would not have been possible without CIFAR fostering collaboration on quantum materials within Canada and internationally, “It’s really a pure CIFAR story.”

Bonn adds that CIFAR’s long-term support of collaborations on materials development and many experimental techniques to study the materials has advanced the field. “The UBC-Sherbrooke collaboration is a particularly successful and long-running example, with each new experimental discovery pushing harder on further development of the materials samples used in the experiments,” he said.

CIFAR President and CEO Dr. Alan Bernstein said, “This breakthrough is an example of how sustained, global collaboration that brings together diverse expertise from across the world is the most powerful way to advance science and address important sustainability challenges.”

Prof. Jacques Beauvais, Vice-President, Research, Innovation and Entrepreneurship said, “This discovery proves once more the extremely high quality of Prof. Taillefer’s research. He and his team have contributed to our success in the inaugural competition of the Canada First Research Excellence Fund. This success is consolidated by the recent creation of the Quantum Institute.”

The Canadians are justifiably pumped up on their breakthrough. The Université de Sherbrooke and the University of British Columbia received a total of $100 million from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund last year to support research on quantum materials and quantum technologies.

The work has passed peer review and folks are likely replicating the research. It looks like the Canadians did it. Lets hope physics cooperates and it works this way as more research scales it up.