Nov

13

A New Model For Ultra Efficient Solar Cell Construction

November 13, 2013 | 1 Comment

Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania and Drexel University have experimentally demonstrated a new model for photovoltaic solar cell construction with perovskite crystals. The new idea may ultimately make photovoltaic cells less expensive, easier to manufacture and more efficient at harvesting energy from the sun.

The study was led by professor Andrew M. Rappe and research specialist Ilya Grinberg of the Department of Chemistry in Penn’s School of Arts and Sciences, along with chair Peter K. Davies of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering in the School of Engineering and Applied Science, and professor Jonathan E. Spanier, of Drexel’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering.

The effort to drive to high efficiency with lower costs has sent chemistry, materials science and electronic engineering researchers on a quest to boost the energy-absorption efficiency of photovoltaic devices. So far the existing techniques are running up against limits set by the laws of physics.

The research group’s study paper has been published in the journal Nature.

Existing solar cells all work in the same fundamental way: they absorb light, which excites electrons and causes them to flow in a certain direction causing an electric current. But to establish a consistent direction of their movement, or polarity, solar cells need to be made of two materials. Once an excited electron crosses over the interface from the material that absorbs the light to the material that conducts the current, it can’t cross back, giving it a direction.

Professor Rappe describes the study background, “There’s a small category of materials, however, that when you shine light on them, the electron takes off in one particular direction without having to cross from one material to another. We call this the ‘bulk’ photovoltaic effect, rather than the ‘interface’ effect that happens in existing solar cells. This phenomenon has been known since the 1970s, but we don’t make solar cells this way because they have only been demonstrated with ultraviolet light, and most of the energy from the sun is in the visible and infrared spectrum.”

Finding a material that exhibits the bulk photovoltaic effect for visible light would greatly simplify solar cell construction. Moreover, it would be a way around an inefficiency intrinsic to the interfacial solar cell route, known as the Shockley-Queisser limit, where some of the energy from photons is lost as electrons wait to make the jump from one material to the other.

Rappe continues, “Think of photons coming from the sun as coins raining down on you, with the different frequencies of light being like pennies, nickels, dimes and so on. A quality of your light-absorbing material called its ‘bandgap’ determines the denominations you can catch. The Shockley-Queisser limit says that whatever you catch is only as valuable as the lowest denomination your bandgap allows. If you pick a material with a bandgap that can catch dimes, you can catch dimes, quarters and silver dollars, but they’ll all only be worth the energy equivalent of 10 cents when you catch them.

“If you set your limit too high, you might get more value per photon but catch fewer photons overall and come out worse than if you picked a lower denomination. Setting your bandgap to catch only silver dollars is like only being able to catch UV light. Setting it to catch quarters is like moving down into the visible spectrum. Your yield is better even though you’re losing most of the energy from the UV you do get,” Rappe explained.

Back to the bulk effect – as no known materials exhibited the bulk photovoltaic effect for visible light, the research team turned to its materials science expertise to devise how a new one might be fashioned and its properties measured.

Starting more than five years ago, the team began theoretical work, plotting the properties of hypothetical new compounds that would have a mix of the useful traits. Each compound began with a “parent” material that would impart the final material with the polar aspect of the bulk photovoltaic effect. To the parent, a material that would lower the compound’s bandgap would be added in different percentages. These two materials would be ground into fine powders, mixed together and then heated in an oven until they reacted together. The resulting crystal would ideally have the structure of the parent but with elements from the second material in key locations, enabling it to absorb visible light.

Professor Davies takes up the explanation, “The design challenge was to identify materials that could retain their polar properties while simultaneously absorbing visible light. The theoretical calculations pointed to new families of materials where this often mutually exclusive combination of properties could in fact be stabilized.”

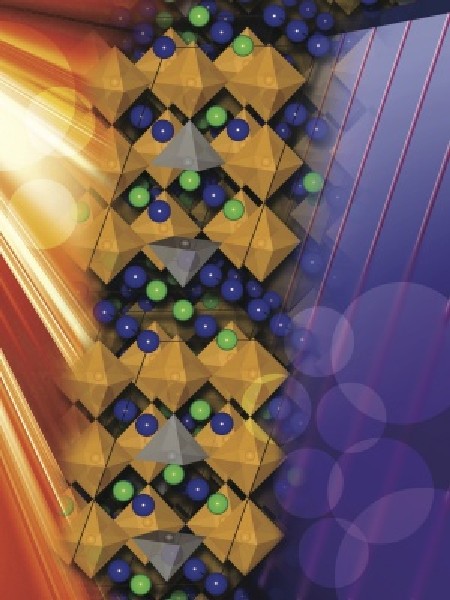

The structure of the team’s material is something known as a perovskite crystal. While most light absorbing materials have a symmetrical crystal structure, meaning their atoms are arranged in repeating patterns up, down, left, right, front and back the structure makes the materials non-polar; all directions “look” the same from the perspective of an electron, so there is no overall direction for them to flow.

A perovskite crystal has the same cubic lattice of metal atoms, but inside of each cube is an octahedron of oxygen atoms, and inside each octahedron is another kind of metal atom. The relationship between these two metallic elements can make them move off center, giving directionality to the structure and making it polar.

Rappe said, “All of the good polar, or ferroelectric, materials have this crystal structure. It seems very complicated, but it happens all of the time in nature when you have a material with two metals and oxygen. It’s not something we had to architect ourselves.”

After several failed attempts to physically produce the specific perovskite crystals they had theorized, the researchers had success with a combination of potassium niobate, the parent, polar material, and barium nickel niobate, which contributes to the final product’s bandgap.

The researchers used X-ray crystallography and Raman scattering spectroscopy to ensure they had produced the crystal structure and symmetry they intended. They also investigated its switchable polarity and bandgap, showing that they could indeed produce a bulk photovoltaic effect with visible light, opening the possibility of breaking the Shockley-Queisser limit.

Moreover, the ability to tune the final product’s bandgap via the percentage of barium nickel niobate adds another potential advantage over interfacial solar cells.

Professor Spanier explores the significance with, “This family of materials is all the more remarkable because it is composed of inexpensive, non-toxic and earth-abundant elements, unlike compound semiconductor materials currently used in efficient thin-film solar cell technology.”

Of note participation and contribution to the study work includes Gaoyang Gou of Penn Chemistry; D. Vincent West, David Stein and Liyan Wu of Penn Materials Science and Engineering; and Maria Torres, Andrew Akbashev, Guannan Chen and Eric Gallo of Drexel Materials Science and Engineering.

The team’s new model for photovoltaic production could be very significant as scaling occurs. It sounds like a very good start for an immense market if scale, cost and efficiency work out.

Comments

1 Comment so far

It seems there’s yet another announcement like this every few days. It’s great news, but when will it accelerate to have some tangible impact for the general populus? I eagerly await high efficiency, low cost solar panels with a payback of much less than 10 years (assuming they last that long). Then finally, we all might have a chance of becoming self-sufficent and avoid having to buy energy at extortionate cost from the major suppliers. Until then, solar energy wll remain an expensive luxury with minor impact for the vast majority.