Nov

10

A Better Lithium Battery With a Little Hydrogen

November 10, 2015 | Leave a Comment

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) scientists have found that lithium ion batteries operate longer and faster when their electrodes are treated with hydrogen. Through experiments and calculations, the LLNL team discovered that hydrogen-treated graphene nanofoam electrodes in the lithium ion batteries show higher capacity and faster transport.

The growing demand for energy storage emphasizes the urgent need for higher-performance batteries. Several key characteristics of lithium ion battery performance – capacity, voltage and energy density – are ultimately determined by the binding between lithium ions and the electrode material. Subtle changes in the structure, chemistry and shape of an electrode can significantly affect how strongly lithium ions bond to it.

Lithium ion batteries (LIBs) are a class of rechargeable battery types in which lithium ions move from the negative electrode to the positive electrode during discharge and back when charging.

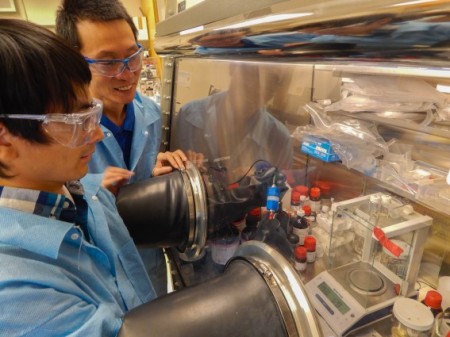

Morris Wang, an LLNL materials scientist and co-author of a paper published Nature Scientific Reports said, “These findings provide qualitative insights in helping the design of graphene-based materials for high-power electrodes.”

LLNL postdoc Jianchao Ye and Morris Wang work on a lithium ion battery studying the use of hydrogen for longer-lasting batteries. Click image for the largest view. Image Credit: Julie Russell LLNL.

Lithium ion batteries are growing in popularity for electric vehicle and aerospace applications. For example, lithium ion batteries are becoming a common replacement for the lead acid batteries that have been used historically for golf carts and utility vehicles. Instead of heavy lead plates and acid electrolytes, the trend is to use lightweight lithium ion battery packs that can provide the same voltage as lead-acid batteries without requiring modification of the vehicle’s drive system.

Commercial applications of graphene materials for energy storage devices, including lithium ion batteries and supercapacitors, hinge critically on the ability to produce these materials in large quantities and at low cost.

However, the chemical synthesis methods frequently used leave behind significant amounts of atomic hydrogen, whose effect on the electrochemical performance of graphene derivatives is difficult to determine.

Yet Livermore scientists did just that. Their experiments and multiscale calculations reveal that deliberate low-temperature treatment of defect-rich graphene with hydrogen can actually improve rate capacity. Hydrogen interacts with the defects in the graphene and opens small gaps to facilitate easier lithium penetration, which improves the transport. Additional reversible capacity is provided by enhanced lithium binding near edges, where hydrogen is most likely to bind.

Jianchao Ye, who is a postdoc staff scientist at the Lab’s Materials Science Division, and the leading author of the paper said, “The performance improvement we’ve seen in the electrodes is a breakthrough that has real world applications.”

To study the involvement of hydrogen and hydrogenated defects in the lithium storage ability of graphene, the team applied various heat treatment conditions combined with hydrogen exposure and looked into the electrochemical performance of 3-D) graphene nanofoam (GNF) electrodes, which are comprised chiefly of defective graphene. The team used 3-D graphene nanofoams due to their numerous potential applications, including hydrogen storage, catalysis, filtration, insulation, energy sorbents, capacitive desalination, supercapacitors and LIBs.

The binder-free nature of graphene 3D foam makes them ideal for mechanistic studies without the complications caused by additives.

LLNL scientist Brandon Wood, who directed the theory effort on the paper said, “We found a drastically improved rate capacity in graphene nanofoam electrodes after hydrogen treatment. By combining the experimental results with detailed simulations, we were able to trace the improvements to subtle interactions between defects and dissociated hydrogen. This results in some small changes to the graphene chemistry and morphology that turn out to have a surprisingly huge effect on performance.”

The research suggests that controlled hydrogen treatment may be used as a strategy for optimizing lithium transport and reversible storage in other graphene-based anode materials.

Looks good, sounds good. The remains a few question though. So far producers have been building batteries seeking to keep out the hydrogen, so what is the difference from the new lab process and the commercial scale process and how does an improved process get integrated into a production line?

We hope this follows through to better batteries. Your humble writes seldom gets the advertised life from commercial lithium-ion batteries, and you’re likely not either.