Jan

22

A Look At Marginal Lands For Biofuel Production

January 22, 2013 | 1 Comment

The research paper has been published in Nature, available behind their pay wall, with a longer form abstract and a downloadable supplementary information pdf.

Ilya Gelfand, lead author and MSU postdoctoral researcher sets up the topic with, “Understanding the environmental impact of widespread biofuel production is a major unanswered question both in the U.S. and worldwide. We estimate that using marginal lands for growing cellulosic biomass crops could provide up to 215 gallons of ethanol per acre with substantial greenhouse gas mitigation.”

Marginal land is the productive area between the waste land that will support essentially nothing worthwhile growing and the crop land where the crops, gardens, orchards and other plant production can be husbanded profitably. Today, some of the marginal land is committed to grazing cattle, wildlife habitat, woodcutting, and other very low-income pursuits.

Ideas about of making better use of marginal land have been around for decades. MSU wants credit as the first study to provide an estimate for the greenhouse gas benefits as well as an assessment of the total potential for these lands to produce significant amounts of biomass.

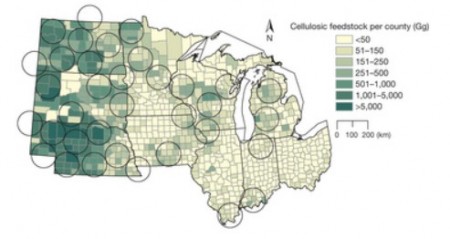

The study is limited in scale to 10 midwestern states. Great Lakes Bioenergy researchers from MSU and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) used 20 years of data from MSU’s Kellogg Biological Station LTER site to characterize the comparative productivity and greenhouse gas impacts of different crops, including corn, poplar, alfalfa and old field vegetation.

To get closer to a workable economic model the team used a supercomputer to identify and model biomass production that could grow enough feedstock to support a local biorefinery with a capacity of at least 24 million gallons per year. The final tally of 5.5 billion gallons of ethanol represents about 25 percent of Congress’ 2022 cellulosic biofuels target, said Phil Robertson, co-author and MSU professor of crop, soil and microbial sciences.

Roberson highlights the results with, “The value of marginal land for energy production has been long-speculated and often discounted. This study shows that these lands could make a major contribution to transportation energy needs while providing substantial climate and – if managed properly – conservation benefits.”

The study is also first to show that grasses and other non-woody plants that grow naturally on unmanaged lands are sufficiently productive to make ethanol production worthwhile. Conservative numbers were used in the study, and production efficiency could be increased by carefully selecting the mix of plant species, Robertson added.

Cesar Izaurralde, PNNL soil scientist and University of Maryland adjunct professor addresses the political angle with, “With conservation in mind, these marginal lands can be made productive for bioenergy production and, in so doing, contribute to avoid the conflict between food and fuel production.”

The team, academic in nature, overlooks the inevitable likelihood that cropland operators will shift to the highest net income production. Once a processing plant gets up and running the best materials at the lowest cost will be at the gates each morning.

It’s still very intriguing. How the economics, markets, competition and other human, social and political factors weigh in isn’t well thought through by any academics yet.

There are some quick positive points as benefits for using marginal lands. New revenue for farmers and other landowners. No indirect land-use effects, where land in another part of the globe is cleared to replace land lost here to food production. No carbon debt from land conversion if existing vegetation is used or if new perennial crops are planted directly into existing vegetation.

It looks like the exercise was not from a grant, but was funded primarily by the Department of Energy’s Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center, the National Science Foundation and MSU AgBioResearch. Additional researchers from the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and the University of Maryland contributed to this study.

One would think the study offers but a fraction of the total land area possible in the U.S.; perhaps 3 or 4 times more production is out there. But the problem isn’t the science, it’s the attracting ten of thousands of farmers and land owners, shifting millions of acres of land in use, capitalizing the planting, cultivation, harvesting and transport to billons of dollars of investment in infrastructure and facilities.

It a good idea whose time to come needs a lot more thought and research.

Comments

1 Comment so far

Marginal lands are only marginal in your eyes. From the environmental standpoint, it’s the only place left for the natural world to continue. Maybe we should be China (or many parts of Europe, like France) where there are few or no birds remaining. If we utilize the planet fenceline-to-fenceline, that’s what we will get.

I’m all for plenty of energy in the US, but if we end up with a billion people and want endless energy, we’ll have an urban landscape across the entire east…what’s not brick and mortar will be fields of “biomass.” The equation is roughly people x demand = impact, so it’s obvious there two main drivers.

So, the question is, does anyone give a damn about the natural world?

JP Straley